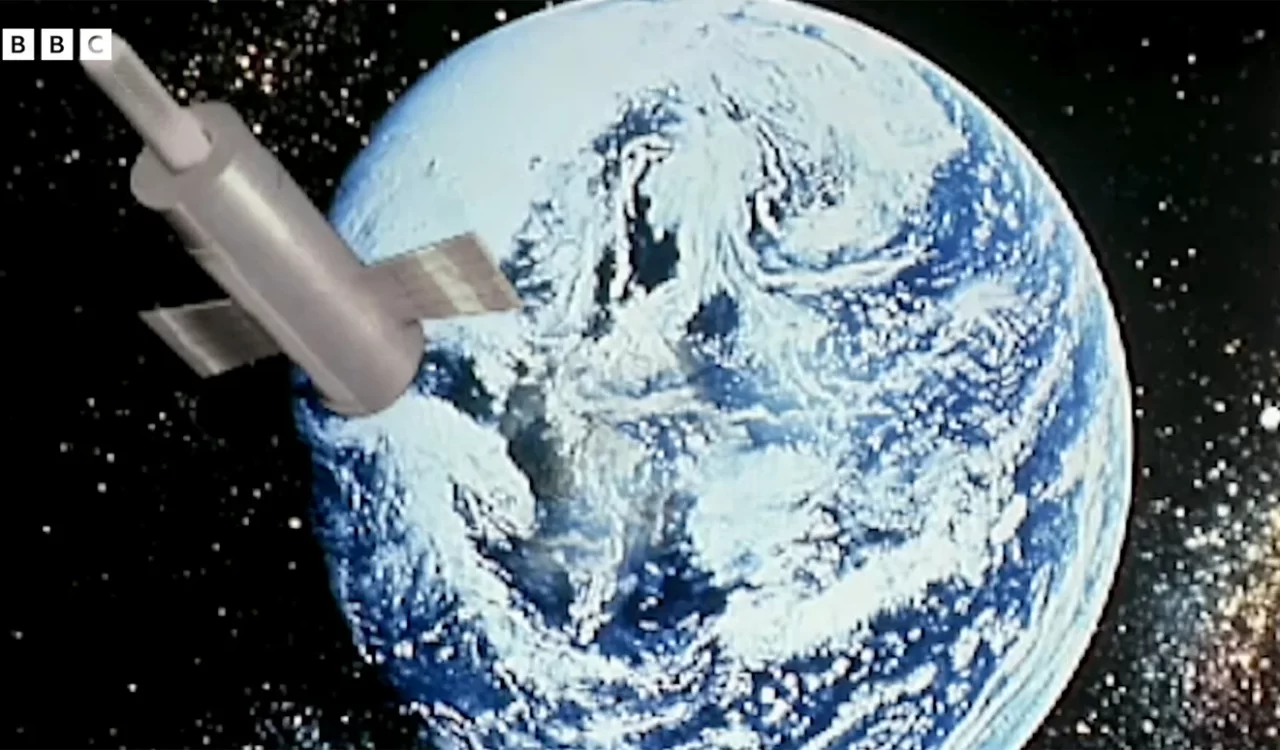

Vladimir Syromiatnikov’s bold attempts to light up Siberia with a space mirror captured global attention. The BBC’s Tomorrow’s World reported on an ambitious experiment that was launched on 4 February 1993.

It sounds like a scheme a James Bond villain might hatch: launching a giant mirror into orbit to harness the Sun’s rays, then redirecting them to beam down on a target on Earth. Yet this was exactly what the Russian space agency Roscosmos attempted to do on 4 February 1993.

But the aim of the Znamya (meaning banner in Russian) project was not a dastardly plot to hold the world to ransom. Its more utopian goal, as presenter Kate Bellingham explained on BBC Tomorrow’s World before Znamya’s launch, was “to light up Arctic cities in Siberia during the dark winter months”.

Essentially, it would try to switch the Sun back on again for Russia’s polar regions after night fell.

Even today this seems a novel concept, yet the idea of using mirrors in space to reflect light onto the Earth’s surface was not actually a new one. Back in 1923, German rocket pioneer Hermann Oberth had proposed it in The Rocket into Planetary Space. His self-published book – based on a PhD thesis which Heidelberg University had rejected for seeming too implausible – demonstrated mathematically how a rocket could leave the Earth’s orbit. Among the other ideas covered in the publication were the potential effects on the human body of space travel, how satellites could be launched into orbit, and, crucially, the concept of creating a grid of colossal adjustable concave mirrors that could be used to reflect sunlight onto a concentrated point on the Earth. Oberth reasoned that this illumination could help avert disasters – like the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 – or assist with the rescue of their survivors. Oberth also speculated that space mirrors could be used to clear shipping lanes by melting icebergs or even to manipulate the Earth’s weather patterns.

This space mirror idea was taken up again by German physicists during World War Two. At the Nazi weapons research centre in Hillersleben, scientists worked on a design to build a terrifying reflective orbiting weapon called the Sonnengewehror Sun gun in German. In 1945, Time magazine reported that captured German scientists had told US Army interrogators that the Sonnengewehr was meant to act as a death ray, refocusing light from the Sun to set fire to cities or boil away water in lakes. Despite facing evident scepticism from their US interrogators as they handed over their technical drawings, the German scientists had believed that their Sun gun could be operational in 50 years, the chief of Allied technical intelligence, Lieutenant Colonel John Keck, told reporters at the time.

Giant orbiting mirrors could illuminate the night sky, enabling farmers to plant or harvest 24 hours a day

In the 1970s, another German‐born rocket engineer, Dr Krafft Ehricke, again began looking at the concept. Ehricke had been a member of Germany’s V-2 rocket team during World War Two. At the end of the war, he surrendered to the US and was recruited as part of Operation Paperclip, wherein 1,600 scientists, engineers and technicians deemed to be valuable were shielded from prosecution, spirited out of Germany, and allowed to continue their work in the US.

Ehricke became part of the US space programme, and in the 1970s he returned to the idea of building a mirror in space. In 1978, he wrote a paper detailing how giant orbiting mirrors could illuminate the night sky, enabling farmers to plant or harvest 24 hours a day, or could be used to deflect sunlight down onto solar panels on Earth to be converted into electricity on demand. He called this idea Power Soletta.

Ehricke, a space-travel enthusiast from childhood and a long-time proponent of colonising other planets, died in 1984 without seeing Power Soletta come to fruition. But he would get his long-desired space flight posthumously when his cremated remains were launched into Earth’s orbit in 1997 along with Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry and 1960s counterculture psychologist Timothy Leary.

Throughout the 1980s, Nasa looked repeatedly at the concept of generating solar power by harnessing sunlight with an orbiting mirror system called Solares, but despite government interest the project was never able to secure funding. However, in Russia the idea of solar mirrors took root.

Sailing through space

At the time, a Russian scientist called Vladimir Syromiatnikov was investigating whether large reflective solar sails could be attached to a spaceship. Syromiatnikov was a pioneering figure in space engineering breakthroughs. He had worked on the Vostok rocket, the world’s first crewed spacecraft that took Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin into space in 1961. He also developed an ingenious spacecraft docking mechanism, the Androgynous Peripheral Assembly System (APAS). This was used in July 1975 in the Apollo-Soyuz test project, the first joint space flight by the then Cold War enemies, the US and the USSR, in which a US module carrying three astronauts successfully linked with a Soviet Soyuz capsule carrying two cosmonauts in orbit. His APAS was later used to enable US shuttles to dock with the Russian Mir space station and is still used for docking at the International Space Station.

Syromiatnikov thought that if solar sails were attached to a spacecraft they could use the Sun in a similar fashion to how ships’ sails use the wind. If the reflective sails could be angled correctly then photons, particles of energy coming from the Sun, could bounce off their mirror-like surfaces and gently propel the craft forward through space without it having to burn any fuel.

However, in Russia during the post-Soviet era, getting funding for ambitious space projects like Syromiatnikov’s was difficult unless they could demonstrate a clear economic goal. So Syromiatnikov decided to repurpose his concept. He thought that reflective solar sails on a spacecraft in orbit could act as a mirror, with the craft’s thrusters used to angle the sails and keep them in sync with the Sun’s position.

That mirror could be used to beam down light on Russia’s polar regions where the days are extremely short in the winter, illuminating areas shrouded in darkness. The extra sunlight would extend the working day and increase the productivity of farmlands. He also envisioned that the bonus sunshine could reduce the cost of electrical lighting and heating for the area and add to the wellbeing of people in the region.

This turned out to be an idea that the government could get behind. And so, funded by the Space Regatta Consortium, a group of Russian state-owned companies and agencies, and overseen by the Russian space agency Roscosmos, Syromiatnikov began work on making the Znamya space mirror a reality.

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC’s unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Subscribe to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

The first prototype built, Znamya 1, wasn’t actually sent into space, but remained on Earth to be tested so that Syromiatnikov could iron out any technical problems. Znamya 2 was to be the first to go into orbit. Its mirror was made from thin sheets of aluminised Mylar, a lightweight highly reflective material which was thought to be sturdy enough to survive the hostile conditions in space. It was designed to unfurl in eight sections into a circular shape from a rotating central drum mechanism and stay in that form through centrifugal force.

“During the flight the reflector is wrapped tightly around the body of the craft, and to open it the craft will have to spin round rapidly forcing it out like an umbrella,” explained the BBC’s Bellingham to TV viewers in 1992. “The trick is that at this height the 20m-wide reflector will then be able to capture the Sun’s rays which normally bypass the Earth and reflect them down onto the dark side of our planet.”

Syromiatnikov’s plan was to have multiple Znamya launches, each one with a larger mirror that burned up as it came back to Earth. Russian engineers would be able to study how Znamya’s thin reflective sheets performed when they were activated in space, and perfect his design. This would lead to the launch of a permanent Znamya with a massive 200m-wide reflector that would stay in orbit around Earth.

Even brighter than the Moon

The ultimate ambition was to have a grid of up to 36 of these giant mirrors in space with the ability to pivot, enabling them to keep the reflected light targeted on the same spot. A single reflector could be used to light up a peculiar area. “On a clear night the space reflector could illuminate an area the size of a football stadium, bringing some light relief to the long winter nights,” said Bellingham. Or multiple reflectors could focus light together to bring greater brightness or illuminate a bigger region. It was estimated that the combined space mirror grid would be able to reflect light 50 times brighter than the Moon and illuminate an area up to 50 miles (90km) across.

On 27 October 1992, the project was ready, and the crewless spacecraft Progress M-15 launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, with Znamya 2 on board. After the cargo supply craft docked with the Russian space station, Mir’s crew fitted the drum containing the folded reflective solar sheets into position on the Progress spacecraft. Znamya 2 was due to be trialled towards the end of the year, but its deployment was delayed while the Mir crew conducted tests for other upcoming missions. On 4 February 1993, they were finally ready to put the plan into action.